Many companies look to WeChat as the model for the next phase of online platforms. Internet companies thrive on the network effects of platforms and many want to create, own and control one. Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook have provided ample evidence of the value you can create and capture if you do.

The latest iteration of mobile platforms, which emerged from China, is not a new operating system or hardware platform. WeChat was launched as a messaging app with social-networking features by Tencent in 2011 and now has 600 million active, mostly Chinese speaking users. It has quickly added more functionality and partnered with many other services. As a developer you can launch your HTML5 game inside WeChat (which is how they get around the App Store restrictions on remote-loading executable code).

WeChat is certainly a big contender in the global messaging war, but what makes other messaging services view it with envy is how it has turned itself into the most important platform in the world’s largest country. In 2013 it launched a payment service, which on the eve of the Chinese New Year 2015 was used for over one billion peer-to-peer transactions. If you’re Chinese, you’re likely to order your taxi on WeChat. Uber’s biggest challenge in China is that it’s not on WeChat, whereas its primary competitor Didi Kuadi is. Weidian offers an e-commerce platform on WeChat with 28 million stores.

Earlier this year Facebook hired David Marcus from PayPal to head up the Messenger team, a move many view as an attempt to build a WeChat for the West (or the rest of the world). For good measure and to hedge its bet, Facebook also acquired WhatsApp for a cool $19 billion. It’s not hard to understand why the social-media giant is looking to China. The average revenue per user (ARPU) of WeChat is $7, Facebook‘s is $2.50 (worldwide), while WhatsApp’s ARPU is $1.

Many other messenger apps are similarly building platforms with some success in certain regions, such as LINE in Japan. It’s a crowded space.

However, in emerging markets which still lack some fundamental enabling e-commerce infrastructure, like electronic payment services and reliable logistics, there is an opportunity to do something similar based on products other than messaging.

This is what Go-Jek, an Indonesian startup on the verge of becoming the country’s first unicorn, seems to be accomplishing.

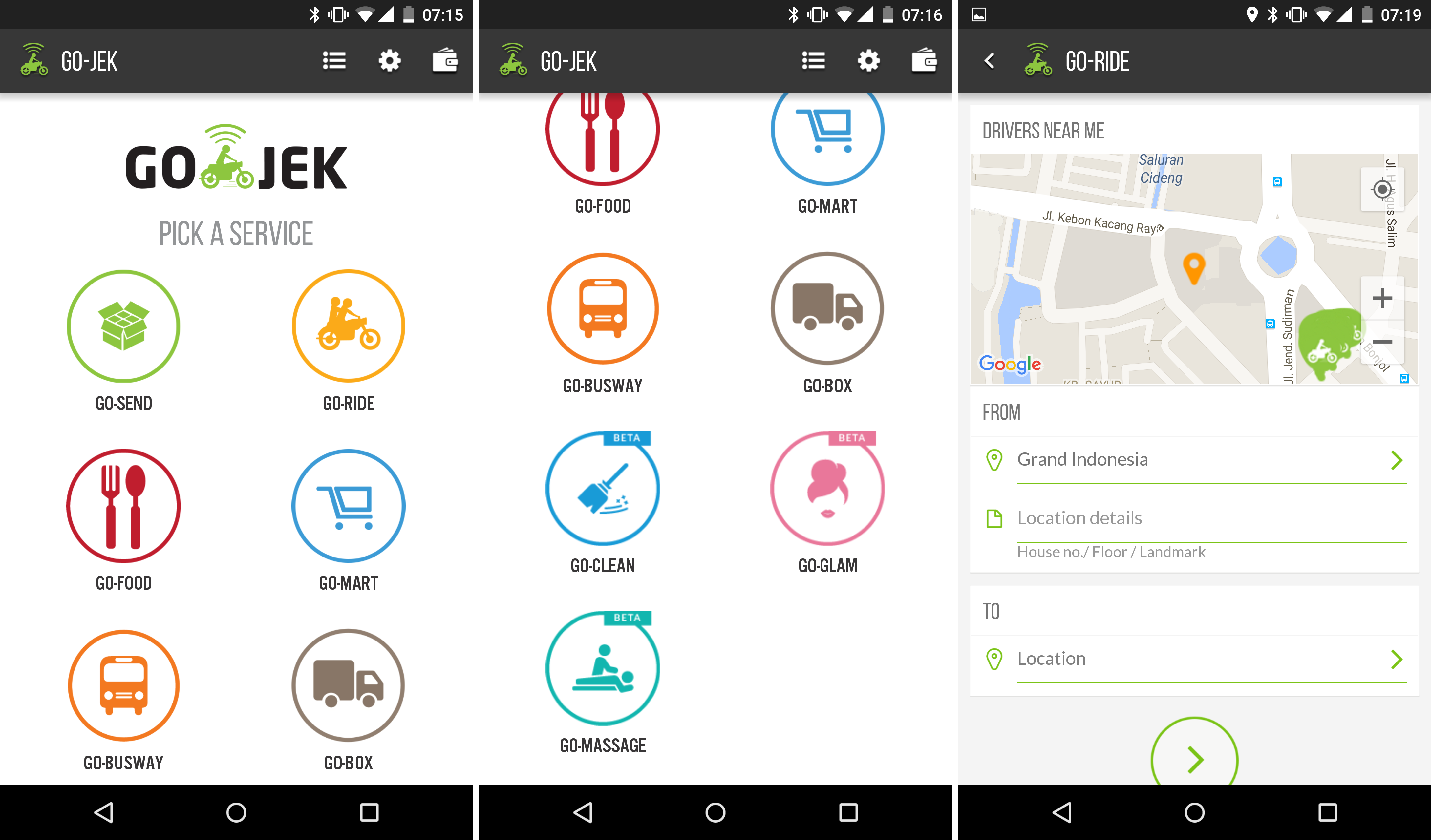

Go-Jek started out as an Uber for ojek, the ubiquitous motorcycle taxis and quickest mode of transportation on Jakarta’s crowded streets. It has quickly expanded to offer other services such as courier, food and grocery delivery, even massages and house cleaning on demand. Recently it launched GoBox, a moving service. Beyond being a transportation company, it is building a platform of services around logistics.

Most importantly, Go-Jek is building a payment service. Payments are complex in Indonesia, with credit card penetration at only 7% and cash-on-delivery a common but inconvenient and unreliable way to pay for online purchases. Other than cash and credit, there is a long list of competing providers of bank transfers, e-cash, vouchers etc. For retailers and consumers alike it’s daunting.

If Go-Jek can solve both payments and instant delivery, it has a great opportunity to build a dominating online platform for Indonesia that other players will want and have to build on top of. Whether the team has the ambition and technical skill to open it up to others remains to be seen.

The West looks at China as a place that copies innovations from the US and, to an extent, Europe and Japan, but that is becoming an outdated view. Japan was once viewed similarly before it quickly became the leading source of innovation in industry after industry. WeChat is one indicator that the online market in China is currently going through a similar phase. Following China’s lead, other emerging markets will increasingly become a source of innovation which will benefit everyone.